VRT — Vehicle Registration Tax — is essentially a hold-over from the days when Irish governments used taxes to protect and promote indigenous industry, not to mention generate a hefty revenue stream for the exchequer. If you're wondering how VRT is calculated, read on to learn more.

When it comes to cars, these taxes used to be loaded heavily onto any car coming into the State that wasn’t built here — hence the proliferation of local assembly factories from the 1950s onwards, as the taxes didn’t apply to cars coming in in kit form.

By the 1980s, such taxes were, effectively, becoming illegal under Ireland’s membership of the EEC, the forerunner to the EU, and so while they were technically dropped, a new form of tax was introduced, called Vehicle Registration Tax. While it’s not technically a tax on imports, so that it can get around EU free trade regulations, that’s effectively what it is — any car being brought into the State for the first time, new or used, must have its VRT paid, or it’s not legal to drive on Irish roads.

So, how is VRT calculated?

Up to the 2008, there were three VRT rates — for cars with engines of less than 1,400cc, for those with engines between 1,400cc and 1,900cc, and above 1,900cc. The rates varied from 22.5 per cent of the car’s wholesale price (for a new car) to 30 per cent for the biggest engines. If it was an imported used car, then the VRT was calculated not on the actual price paid, but on the ‘Open Market Selling Price’ — or in other words, the price that the Revenue Commissioners reckon the car would have sold for had it been sold in Ireland.

How is VRT now calculated?

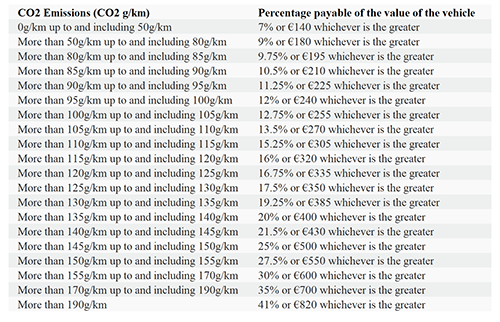

From 2008, all that changed and VRT became predicated on a car’s CO2 emissions, with a sudden proliferation of bands. Those bands have been successively adjusted and amended to take account of generally lower levels of CO2 and today we have 20 bands, starting at 7 per cent of the wholesale or OMSP price for cars with CO2 emissions of less than 50g/km (effectively limited to fully-electric cars and a handful of the most efficient plug-in hybrids) rising to a maximum of 41 per cent of the wholesale or OMSP price for cars with CO2 emissions above 190g/km. You can see the full breakdown on the table below.

There are other variations in VRT. The above calculations are known as Category A, which is meant for privately-owned passenger cars. There’s also a Category B, which is primarily aimed at commercial vehicles not exceeding 3.5-tonnes. In Category B, there are two versions of VRT — most vehicles will pay a flat rate of 13.3 per cent of their OMSP or wholesale price, but in a few cases there’s a single €200 payment. Camper vans also fall into this category.

There’s also a Category C, which is meant for heavy goods vehicles, buses, and tractors but which also covers classic cars, which are defined as being at least 30 years old at the time of their entry into the State. These are charged a single flat payment of €200.

Category D covers ambulances, bin lorries, road sweeping machines, fire engines, and road rollers, other road construction machinery, and agricultural machinery, and is exempt from any VRT payment.

Finally, there’s Category M, which is for motorbikes, and on those you’ll pay €2 per engine cc up to 350cc, and €1 for each additional cc above that.

And electric vehicles?

Oh, wait — there are other rules for electric cars. For the moment — and with a theoretical cut-off date of December 31st 2023, there’s the VRT rebate for electric vehicles, which gives you as much as €5,000 off the cost of their VRT. Essentially, that’s free VRT for many electric vehicles, but there are limits. Electric vehicles with a new price of more than €50,000 don’t get any VRT rebate, while those priced between €40,000 and €50,000 get a tapering rebate — the €5,000 rebate is reduced by a percentage of the car’s price above the €40,000 mark.

Want more complication?

You’ve got it. VRT also includes an element of the car’s NOX emissions — nitrogen oxides, the unpleasant gases, which are hugely harmful to human health, and which were at the heart of the whole diesel emissions scandal which blew up in 2015. The NOX charge is calculated on the emissions of the gases, and costs €5 per mg/km of NOX up to 40mg/km, then €15 per mg/km up to 80mg/km, and then €25 per mg/km above that. For diesel cars, there’s a maximum possible NOX charge of €4,850 (which is automatically applied if there are no official NOX figures for the particular car in question, which can be the case for some older models) and €600 for petrol-engined car (which tend to be very low in NOX anyway).

Brexit and Northern Ireland cars

There is another charge to pay, which is VAT. In theory, you don’t have to pay VAT when importing a used car from within the EU, but of course since the dreaded Brexit vote, the UK — our primary source of imported used cars because they’re the only other right-hand drive market in Europe, unless you count Malta and Cyprus — has been outside the EU, so VAT charges apply. Customs fees also apply, which are charged at ten per cent of the vehicle’s price plus shipping costs.

There are some loopholes to that — if you’re buying a used car from Northern Ireland, while you’ll still have to pay VRT, thanks to NI’s position of being half-in, and half-out of the EU you won’t have to pay VAT nor customs duty, as long as you can show that the car you’re buying was purchased from a dealer or private individual who had it on general sale — in other words, the car wasn’t brought into Northern Ireland especially for you to be able to duck the VAT.

From May 1st 2023, there is also a new rule in the UK, which allows VAT-registered buyers in the EU to claim back VAT from the UK exchequer upon the export of a car to an EU country. That’s not a huge benefit for private buyer — few of us are VAT-registered — but it could be a boon for Ireland’s car dealers, who have seen a traditionally useful source of high-quality used cars effectively strangled by Brexit regulations.

The VAT rebate isn’t a full one — the UK’s new regulations allow you to claw back 16.67 per cent of the original VAT paid on the car — and you’ll still have to pay Irish VAT at 23 per cent, but it’s a significant discount on what you would have previously had to pay.

There are some wrinkles to that — if a used car was in a UK dealer’s stock before the 1st of May 2023, it will still be VAT-able at the full rate, and the rebate doesn’t apply so there may well be some divergence in the values of used cars whose stocking date falls on either side.

Equally, any resurgence in used car imports from the UK would mean that careful history checks — such as those provided by Motorcheck — would have to be made, as there’s a constant danger of written-off cars, or cars with poor history, being ‘dumped’ on the export market.

CO2 Emissions bands